Writing Lab: First Draft (Contraflow Book Series)

August 29, 2005; Monday morning

In the Gulf of Mexico aboard the USS Bataan, the refitted helicopters are now on the deck. The massive 844-foot Wasp-class amphibious assault ship normally carries three dozen helicopters, and a ship’s company of 1,200 sailors and 2,000 marines. Because it served as the PANAMAX flagship, there are no marines and just a few helicopters on board. With the waters of the Gulf of Mexico still rough, the USS Bataan’s commanding officer Captain Tyson sets a course to follow the storm into New Orleans, taking a position just off the coast of Louisiana near the mouth of the Mississippi River about 75 miles south of the city. The crew monitors the cable TV news and radio stations. They are relieved to see and hear the “dodged a bullet” headlines and lead-ins on CNN, Fox, MSNBC and New Orleans’ WWL-AM.

In the Upper 9th Ward, Navy Captain Lafe Dozier, Ensign Trevor Smalls and New Orleans firefighters watch from the rooftop of a multi-story building on Poland Ave. on the grounds of the Naval Support Activities (NSA New Orleans), as six blocks away the water flows over the Inner Harbor Navigational Canal (Industrial Canal) into the Lower 9th Ward.

Lifelong Lower 9th residents Albert Bass and his wife, who rode out the storm near Andry and North Roman Streets in a house built by Albert’s grandfather in 1948, are preparing breakfast when they hear noise coming from the bathroom. Water is coming up through the toilet. Albert goes to the front door, finds water at the top step, and says “It’s happened!” They quickly gather canned goods from the kitchen and head up the stairs to the second floor, as the water follows right behind them. Albert kicks out a bedroom window, but water rushes in to the bedroom. They have only one option left, the attic. Fortunately, his wife finds a rusty steak knife and broken crowbar and the couple climb up into the dark attic and start chipping away at the roof, praying as they desperately try to make a way out.

Twelve miles to the southeast in southern St. Bernard Parish hundreds are riding out the storm at St. Bernard High School, one of the two parish’s high schools turned shelter of last resort. Thinking the worst is over evacuees are loading their cars preparing to go home, when all of a sudden someone shouts “the water is coming!” Everyone runs back into the school. Those who have brought their boats to the shelter run outside and attempt to unhitch them from the trailers. Panic starts to break out.

Eleven miles to the northeast in a section of the parish, on the 1900 block of Aycock Street, Father Dennis Hayes watches from his church’s school building as the water rushes in from the direction of the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MrGO) and rises to the height of the telephone wires in just twenty minutes, submerging all the houses around him in Arabi and the adjacent Lower 9th. He knows that there are many people in those houses and that unless they are very agile and can get up to the attic and break through the roof they are going to die. It is a very sad moment. It usually takes Catholics 15-20 minutes to say five Mysteries of the Rosaries. Father Dennis Hayes says all twenty (five Joyful Mysteries, five Luminous Mysteries, five Sorrowful Mysteries and five Glorious Mysteries) in just ten minutes. It is the only thing he can think of to do.

The same thing was happening throughout the Lower 9th, which is also home to the historic Jackson Barracks, State Command Headquarters for the Louisiana National Guard (LAANG). The linear two-block wide base established in 1834, stretches for a mile from the Mississippi River. A base that also serves as a border, some say buffer, between predominately black Orleans Parish and predominately white St. Bernard Parish. The third floor of a building on the base is being used as a collection point for survivors brought in by boats. But with the first two floors flooded and the disruption of natural gas, the decision is made to relocate JOC Jackson Barracks to the Superdome.

In the Pines Village Neighborhood of New Orleans East, Wilfred Johnson (aka “Blu”), Kim Cardriche, her 19-year old son, 21-year old daughter, 65 year-old mentally challenged aunt and 101-year old aunt are hit by a tsunami like wall of water. Fortunately, they are in one of the few two-story homes in the community, which weathered the storm well; aside from a flooded out first floor. As they assess the damages from a second story window, all they see is rooftops sticking up above the water lines. And all they can hear is screams coming from attics. People are trying to hack their way through the roofs.

Marty Bahamonde, who spent the night in the New Orleans City Hall, receives a transmission saying that NBC reported a hole in the Superdome roof. It is an event that he is witnessing in real time with his own eyes from a nearby three-story parking garage. He gets word to his bosses at FEMA on his Blackberry confirming that portions of the roof are peeling off.

Inside the Superdome, backup electrical generators are running. However, there is no more air conditioning, and only half the original lighting is working. Two large panels from the roof are gone, but because Paul Harris had this very event in mind when he chose his seat under an overhang, he does not have to relocate. With everyone now hearing the storm through breached roof, there are now fears that the entire roof will blow off. To take his mind off his worries Paul walks the hallways of the domed stadium. He is thoughnprohibited from venturing to the third or fourth levels.

A half mile away in the BW Cooper (the Calliope) Housing Development, Kelly Robinson and her family are doing just fine. New Orleanians know that the safest place to be in a hurricane is one of the many fortress-like public housing projects operated by the Housing Authority of New Orleans (HANO). Then the word gets out that there are no police officers in sight.

In the Lakeview Neighborhood, NOFD Captains Paul Hellmers, Gordon Case and Joe Fincher, and six other firefighters watch from an upper floor of the Marina Towers as a 200-foot wide breach on the Orleans Parish side of the 17th Street Canal levee seals the fate of the city of New Orleans. They know the salt water rushing in from Lake Pontchartrain will soon inundate the neighborhoods of Lakeview, West End, Mid City, Hollygrove, Gert Town, Broadmoor, Central City, the Calliope and beyond. At this moment, they know that this event will be bigger than 9/11.

FEMA Urban Search & Rescue (US&R) teams Tennessee Task Force One (TNTF-1), Missouri Task Force One (MOTF-1), Texas Task Force One (TXTF-1), Florida Task Force One (FLTF-1) and Arizona Task Force One (AZTF-1), mostly veterans of the 9/11 deployment, are all en route to Baton Rouge.

Coast Guard Captain Jones and his crew members are having a late breakfast at an IHOP near Lake Charles Regional Airport (LCH), discussing what all Coast Guard personnel knew within days of arriving at Air Station New Orleans; that a catastrophic hurricane could flood the city and there could be tens of thousands of victims who would need to be rescued and recovered.

Down the block at Lake Charles Regional Airport (LCH), Helinet Aviation president Alan Purwin and Vice President -Technical Operations J.T. Alpaugh arrive from Los Angeles’ Van Nuys Airport aboard a private jet. They are scheduled to meet up with their American Eurocopter Astar 350-B2 production helicopter, which is flying in from Teterboro Airport (TEB) in New Jersey. As they prepare their new Cineflex high-definition camera for reconnaissance flight to Southeast Louisiana, they run into Captain Jones and his crew members and present their camera’s capabilities to them. Captain Jones tells Alan and J.T. that he believes their aerial camera will be in demand, but that he cannot validate or help them get it out there. The Coast Guardsmen board into the three HH-65B Dolphin helicopters and lift off for Houma, Louisiana where they plan to rendezvous with the crew commander Lieutenant Olav Saboe and the second Dolphin helicopter sent to Air Station Houston.

August 29, 2005; Monday afternoon

At the Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base (NAS JRB New Orleans) in Belle Chasse, Louisiana, twenty miles south of the New Orleans CBD, emergency management officer Lieutenant Commander Paul Prokopovich, base executive officer Commander Bret Bateman and base commander Captain A.J. Rizzo are inspecting the facility for damages. They find downed trees and minor flooding. More importantly, the two runways are unaffected and can begin receiving aircraft after a minor clean up. Their biggest problem is communication. Landlines are down and cell phones are not working. However, their satellite phones are working, and being used to reach the Louisiana State Office of Emergency Preparedness’ Emergency Operations Center (State EOC) in Baton Rouge to let them know NAS JRB New Orleans is open for business. But the State EOC is saturated with incoming communications. Although the levees are intact near Belle Chasse, further down the Mississippi River, the rest of Plaquemines Parish was devastated. There are reports of live people and dead bodies in trees and entire families being washed out into the Gulf of Mexico.

Thirty miles southwest, all five HH-65B Dolphin helicopters land at Houma-Terrebone Airport (3L1) and fuel up at Charlie Hammond’s Air Service. Mr. Hammond tells them he has more fuel stored in his trucks and will be here 24/7 as long as the Coast Guard needs him. The winds are dying down enough for their Dolphin helicopters to commence search and rescue missions over Greater New Orleans. Captain Jones hands out missions. A crew is tasked to Belle Chasse to check on Air Station New Orleans. Lieutenant Saboe’s crew is tasked to Lower Plaquemines Parish where they find utter devastation, shrimp boats on the highway and whole towns missing. In Violet, Louisisna, they find an adult female with a broken arm. She is hoisted up and will be transported to Meadowcrest Hospital on the Jefferson Parish Westbank. The medical center has no helipad, but it is the closest emergency room. After Captain Jones’ crew offloads the patient in a field next to the hospital, they lift off and head on a mission to assess the conditions at Coast Guard Station New Orleans, in the Bucktown Area of the Jefferson Parish Eastbank on the south shores of Lake Pontchartrain.

Half a mile to the east in Lakeview, NOFD Captain Hellmers and the eight other firefighters launch a rescue mission with a commandeered boat, dropping survivors off at the Hammond Hwy. Bridge, which crosses over the 17th Street Canal. The canal also serves as the border line between Orleans Parish (City of New Orleans) and Jefferson Parish East Banks. Many begin walking along the Lake Pontchartrain levee to Coast Guard Station New Orleans in Bucktown.

Two blocks from the St. Bernard Public Housing Projects, on the 3900 block of Paris Ave., NOFD firefighters Steven Hester and Rodney Cardova, and Operator Paul St. Julien are abandoning Engine House 21, which is rendered useless by more than six feet of water, and are making their way to the Fairgrounds to meet up with 1st Platoon Captain Herman Franklin, 2nd Platoon Captain Quentin Brown, 3rd Platoon Captain Nick Felton and other brethren who pre-staged there yesterday. The Fairgrounds, owned by Churchill Downs Inc., is home to horse racing and the annual New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. Assistant Security Chief Jim Schanbien, along with seven workers, rode out the storm here. The high winds sheered off most of the grandstand roof. But remarkably, none of the glass facing the infield is shattered. The parking lot and maintenance building has been designated to the NOFD personnel and their search and rescue equipment.

Port of New Orleans Harbor Police Dept. (HPD) Corporal Glenn Smith and Officer Chris Lanier leave the Morial Convention Center (MCC) in an F-250 truck to go check on Officer Lanier’s home in St. Bernard Parish. The streets are relatively dry as they drive through the New Orleans CBD, French Quarter, Marigny and Bywater Neighborhoods; all bordering the Mississippi River, the highest points in the city. As they reach the top of the bascule-type St. Claude Ave. Bridge, which spans the Industrial Canal, they see people on rooftops as far as the eye can see. Corporal Smith radios back to their Chief who instructs them to return to the convention center and pick up HPD Corporal Rob Lincoln, Lower 9th Ward native HPD Lieutenant Steven Dorsey and the HPD Boston Whaler with the 90 hp Yamaha motor. A watercraft used mostly for deep sea fishing. They hitch the Whaler to the F-250, head back to the St. Claude Ave. Bridge and launch on the Lower 9th Ward side around 2:00 pm. Houses are floating, cars are bobbing up and down and people are screaming for help. The four men start going rooftop to rooftop.

Louisiana Department of Wildlife & Fisheries Enforcement (LDWF) Lieutenant Colonel Keith LaCaze dispatches a convoy of 62 agents with 31 boats from Baton Rouge to Greater New Orleans. Lifelong St. Bernard Parish resident LDWF Region 8 Supervisor Captain Brian Clark, who spent last night in the State EOC monitoring the storm, informed Louisiana State Senator Walter Boasso about the mission. The convoy is being led by a state police officer and four bridge inspectors checking the structural integrity of the 15-miles of elevated I-10 that spans the Bonnet Carrie Spillway between LaPlace and Kenner, Louisiana. They reach I-10 & Causeway Blvd in Metairie, Louisiana and realize that this is as far as they can go by automobile. Captain Clark and Sergeant Rachel Zechenelly are sent ahead to find an alternative route to the Superdome where other rescue workers are congregated. One route takes them over the Mississippi River on the Huey P. Long Bridge to US90 East to the Crescent City Connection Bridge and into the New Orleans CBD. Another route takes them along the Eastbank Mississippi River levee to Tchoupitoulas Street into the New Orleans CBD. They utilize both routes. After the convoy reaches the Superdome, they are informed by NOFD, NOPD and the Louisiana State Police (LASP) that everything to the east is under water. Fortunately, I-10 East is elevated to just east of the I-610 split, a distance of about four miles. So the LDWF convoy splits into three units: St. Bernard Ave (I-10, exit 236C); Elysian Fields Ave. (I-10, exit 237) and I-10/I-610 eastern split (I-10, exit 239). Dwight Boudreaux, who found shelter in a neighbor’s second story home just two blocks from I-10 exit 237 on Tonti Street, is one of the first to be rescued. He thanks the LDWF agents from Boosier Parish, Louisiana, who had arrived forty-five minutes after the winds died down. As another group of rescue workers drive him to the Superdome on the elevated I-10, Dwight looks down and sees the magnitude of what has happened to his 7th Ward Neighborhood. All he can think about is all the people who need help.

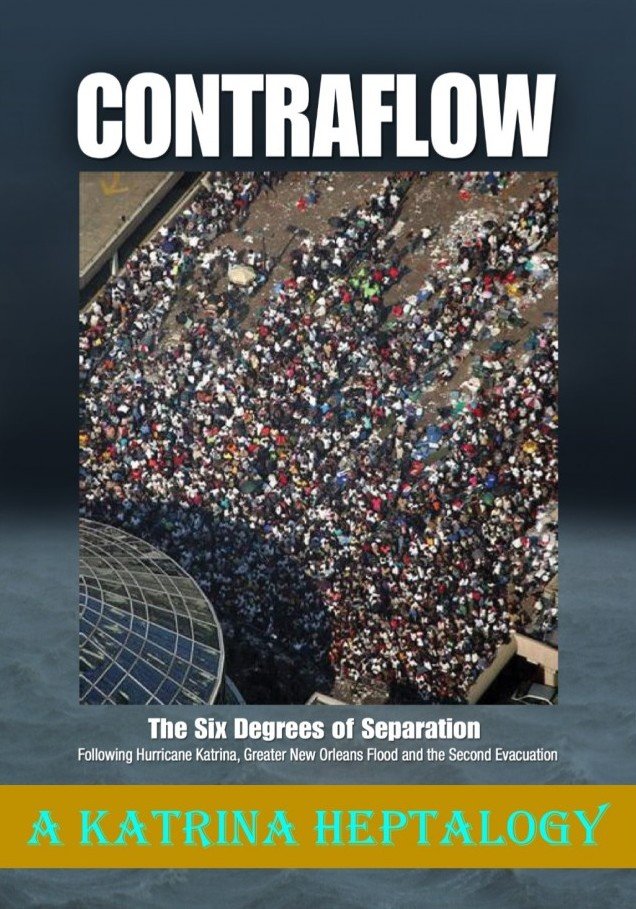

At the Superdome, survivors like Dwight are starting to come in droves bringing horrific stories of losing family members and of being in water up to their necks before being saved by volunteers in small boats. The demographics and dynamics of the crowd are changing drastically. Before the storm, most of the residents stayed in the cultural and political boundaries of their respective ward. But here in the Superdome, the wards are mixing. Paul hears a NOPD officer say he expects a riot by tomorrow, but shrugs it off as paranoia. However, a couple hours later, Paul begins thinking the same thing. He is witnessing the development of a mini-society that mimics William Golding’s classic book Lord of the Flies, a book about a group of shipwrecked kids who form their own government and means to survive. Tension is rising as rumors and misinformation spread. The meal lines, which were forty-five minutes long, are now up to an hour and a half. People begin cutting in line and shoving. The LAANG is starting to lose control.

There are close to eighty NOPD officers assigned to the Superdome from a variety of divisions and units which include Cold Case, High Profile Police Shootings, Homicide, Special Victims Unit (SVU), Child Abuse, Juvenile, instructors and recruits from the Academy. They are positioned in some of the 300-level luxury suites. They know that the LAANG for the most part has no ammunition due to the fact that its Jackson Barracks armory is now underwater in the Lower 9th Ward.

The New Orleans Arena, home to the NBA Hornets, is just across the street to the west and connected by two sky bridges. The special needs patients were brought to the concourse area of the Arena yesterday However, the Tulsa-based DMAT Oklahoma One (OK-1) have not yet arrived to set up triage operations. The constant arrival of survivors means the arrival of more and more injured, sick and infirmed. The City of New Orleans Health Dept medical staff is quickly becoming overwhelmed. The word goes out that a DMAT is needed at the Superdome as soon as possible. The middle link between FEMA and the DMATs, National Disaster Medical System (NDMS), instructs DMAT NM-1 and DMAT NV-1 to depart Houston immediately. Their destination is the Superdome.

At the Calliope Projects, just like everywhere else in America, it is the end of the month. Most of the residents have no money or food. Many in the neighborhood go on a free-for-all, with no police in sight to stop or deter looting. And with no flood waters to hinder movement, many started with Coleman’s Retail Store at Earhart Blvd. & South Broad Street. Then word spread through the Calliope that the Winn-Dixie grocery store on South Claiborne Ave. is open and unstaffed. Many jump in cars, on bikes and on foot and go “make groceries,” and notice more unstaffed stores and buildings like Payless and Universal Furniture Store.

North of Earhart Blvd. across I-10 on the Broad Street Bridge at the massive Orleans Parish Prison (OPP) complex, Rick Mathieu, Jr. is still confined to his prison dorm area on the second floor of Templeman II. Prisoners are yelling to get the attention of the guards. They want food and water, want to know when they will be evacuated, and they want to know if their families are safe. OPP Special Investigative Division officers, the Sheriff’s elite anti-riot force, are tired of hearing the noise. They come into the dorm area and begin spraying mace and shooting bean bags. These are the only authority figures Rick Jr. and the others have seen all day.

Hovering one hundred feet off the ground, Captain Jones, his co-pilot, flight mechanic and rescue swimmer are completing the damage assessment of Coast Guard Station New Orleans in Jefferson Parish and are heading east above the Lake Pontchartrain shoreline passing over University of New Orleans (UNO). Two miles further above Lakefront Airport (NEW), Captain Jones sees the strangest thing. Its control tower atop the terminal is missing an entire wall, exposing a group of men sitting in chairs looking back at them. Captain Jones thinks to himself, “those poor air traffic controllers must have gone through hell.” However, they do not seem to be in any distress, and the facility is relatively dry. The airport lies outside the levee protection system, meaning the surge waters were not trapped by levees allowing them to flow back into Lake Pontchartrain after the storm passed. He then takes note of the destruction of the Louisiana National Guard Aviation facility. No aircraft will return here anytime soon. Captain Jones continues, making a southerly turn for a half a mile and sees a heart-breaking sight above Kim and Blu’s Pines Village and the Little Woods Neighborhoods of New Orleans East. It looks like thousands of people are on rooftops as far as the eye can see. That same wall of water that came up the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet (MrGO) has deposited the Gulf of Mexico into New Orleans East as well. There is no need to use the word “search” anymore. USCG Dolphin helicopter “CGNR 6598” is now on a rescue mission. Captain Jones orders more Dolphins to the area and tells his crew to start hoisting the survivors up one by one. The Coast Guard motto Semper Paratus, Latin for “always ready”, is now being put to the test.

Back at LCH, Alan Perwin and J.T. Alpaugh are feeling good about the “dodged a bullet” reports. However, they had come to Louisiana to test their new HD camera. A little while after Captain Jones and his air crews departed LCH, Alan and J.T. lift off in their AS 350B helicopter and head due east. They reach the western edge of Greater New Orleans and see a damaged water tower. J.T. begins rolling film. He tells Alan “the ICS on the intercom system is hot,” and J.T. begins to document the tape narrating what they are seeing. They come upon a huge fire on film at the Southern Yacht Club in the West End Neighborhood. He has a background in news, but not as a cameraman or reporter. He has been a LAPD reserve police officer since 1990, working on the air patrol division as a tactical flight officer. About ten minutes later they are above New Orleans East filming Captain Jones and his crew performing air rescues. Based on the information being passed out at LCH, Alan and J.T. now realize that the outside world has no clue about what is really happening in New Orleans. The media satellite trucks are limited to the French Quarter and New Orleans CBD, which is not badly damaged or flooded. J.T. tells Alan, “This is our calling. This is what we are here for.” However, they are now feeling a sense of helplessness because their helicopter has no rescue capabilities. But, they know it will take a massive response, so they prepare themselves to be the conduit; the messenger of this mega disaster. They continue to roll film and J.T. continues to narrate. Coast Guard Dolphin helicopters are not designed to carry a lot of people. Depending on the evacuee’s mass and the fuel level, they can take on four to six survivors hoisting them up one at a time. Due to the Dolphin’s capacity, Captain Jones makes a command decision to drop survivors off at nearby dry spots “lily pad,” so they can maximize their fuel consumption and keep hoisting up as many survivors as possible. One of the men in the old control tower looking back at Captain Jones earlier was Lakefront Airport manager Randolph Taylor. He and others who stayed notice what looks like the same Coast Guard helicopter they saw earlier, dropping off people near their airport parking lot. Captain Jones knows this will not be his last off load at this location. An Orleans Levee Board truck is sent out to pick up the survivors.

August 29, 2005; Monday evening

One of the five Dolphin helicopters under Captain Jones’ command is called away on a mission to take Marty Bahamonde on an aerial view of the 17th Street Canal. Marty then takes a second survey, this time flying east over the Industrial Canal, New Orleans East, I-10 Twin Span Bridge and Slidell.

He reports to FEMA the devastating news via his Blackberry that 80% of the city is under water. He then returns to the City EOC on the ninth floor of City Hall where twenty-five members of Mayor Nagin’s team are waiting to hear his report. Everyone is asking about their neighborhoods. Marty requests a map of New Orleans and begins to tell them what he saw; under water, under water, under water, under water, not under water. All you can hear is gasps, groans and crying. Retired Colonel Terry Ebbert, Director of New Orleans Office of Homeland Security & Public Safety, comes up to Marty and says “you have done this before, what do we do now?” Marty tells Ebbert and Mayor Nagin “you must make a list of your critical needs and let the state know what they are so they can direct FEMA to provide help.”

Alan and J.T. are running low on fuel and must break away from filming the Coast Guard rescues over New Orleans East. Overall, they shot 1.5 hours of high definition film. Helinet Interim-CEO David Calvert-Jones, who has heard J.T.’s breathtaking description of the film, is in his Van Nuys Airport (VNY) office talking with CNN. Helinet’s New York City production truck will not arrive for another day or so, and they need a way to upload the high definition film they have just shot. The plan now is for Alan and J.T. to meet a CNN remote satellite truck at Baton Rouge Metropolitan Airport (BTR) about 75 miles to the northwest. They touch down around 8:00 pm and find a disinterested a CNN producer without a HD player. J.T. retrieves their HD player from the helicopter and pops in the film. Everyone’s jaw in the satellite truck drops. J.T. and Alan are watching some of the playback TV feeds as networks like CNN, Fox, MSNBC, CBS and ABC begin to capture the images raw one after another. There will be no more “dodged a bullet” headlines. It was at this moment J.T. believes the country is realizing the extent of what is happening. They both feel a sense of gratification for getting the images out there along with the message of “send help, send it now!”

They fuel the helicopter, park it and begin looking for a place to stay, when J.T. receives a call from an ABC Nightline producer saying Ted Koppel wants to speak with him. Mr. Koppel says, “we are seeing your images and hearing your narration.” J.T. now realizes he is being interviewed by the real Ted Koppel as they drive around Baton Rouge in a borrowed car looking for lodging. It is all now so surreal for the two Southern Californians. They find vacancy at a Courtyard by Marriott on Acadian Thruway, who has some rooms that were recently vacated by a Hollywood film crew that evacuated before the storm. Still feeling the adrenalin they decide to pay a visit to the State EOC where they find very little happening. An aide to Governor Blanco tells them they are not interested in their services or help. J.T. reports back to Van Nuys with the message “the State of Louisiana has everything under control.”

© 2015 All Rights Reserved, M. Darryl Woods dba Treme Press

TCP Responses